Stereotypes have no place in education

March 15, 2018

For as long as I can remember, being a public school student was always something a little embarrassing to admit. Public schools get a bad rep, especially in Hawaii: People talk about bad teachers; people make fun of poorly performing sports teams; nobody will ever expect you to be as smart as an Iolani or Punahou student, and that’s just kind of the way it’s always been. You can be smart, but you go to a public school, and that registers differently in the minds of many people in Hawaii.

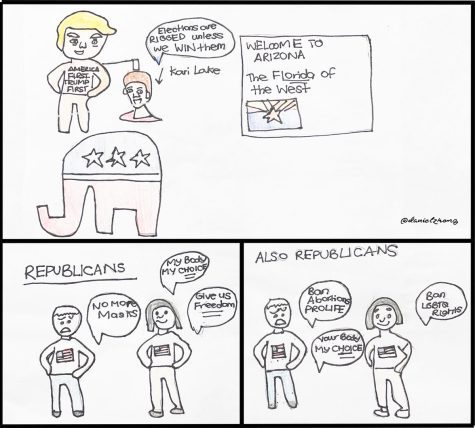

Peter Kay of Aim for Awesome, a website dedicated to “moving to, living in or vacationing in Hawaii” acknowledges the “good” public school students he knows, but later swoops: “I also know some kids that grew up like local hoodlums and are breaking into cars for a living.”

This assertion encompasses what is wrong with the way we talk about public school kids, specifically in our state. By calling a public school student a “hoodlum,” you are enforcing the stereotype that public school students have no future. The stereotype splits public and private schools between poor and rich, deepening the class divide in our society.

According to Christopher and Sarah Lubienski, authors of The Public School Advantage, people often look only at the superficial aspects of schools, such as uniforms and athletics, and not academic statistics.

They write: “As schools are cast as competing businesses in current reforms, families may be influenced by image over academic substance, just as fast food marketing successfully focuses on fun and not nutrition.”

In Hawaii, negative attitudes about public schools are high. 37.65 percent of children attend private schools, nearly one-fifth of the state’s population. It’s the highest percentage in the nation, according to Civil Beat article titled “Living Hawaii: Many Families Sacrifice to Put Kids in Private School” published March 17, 2014.

Many parents in this article use words like “unsafe” and “full of bad crowds” to describe public schools, which is a broad generalization of a diverse group of students. Why do we talk about our students this way? Why do some avoid even associating with public schools at all?

These widespread attitudes may, in fact, have historical racial origins.

Ann Bayer, author of Going Against the Grain: When Professionals in Hawaii Choose Public Schools Instead of Private Schools, studies how people in Hawaii believe that private schools are superior to public schools. She asserts that this comes from how students of elite white families were segregated from others during missionary and plantation times. The other students were thought of as commoners. Theses prejudices still exist today — maybe on an explicit level, but undertones of racism and classism often surround conversations of public vs. private schools.

It is worth noting that academic achievement in Hawaii public schools is, on average, lower than that of schools on the mainland. According to the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, an exam taken by fourth and eighth graders, Hawaii’s average scores were lower than all but five other states. For instance, in 2016 the average science score for eighth graders was 146, with the national average being 153. Despite these scores, stereotypes that perpetuate the myth that public schools are dangerous or fail to educate students only position public school students to fail.

Based on my experience in Hawaii’s public school system, specifically, Kalani High School, what a student learns is based on how much they wish to apply themselves, and has less to do with funding and instruction.

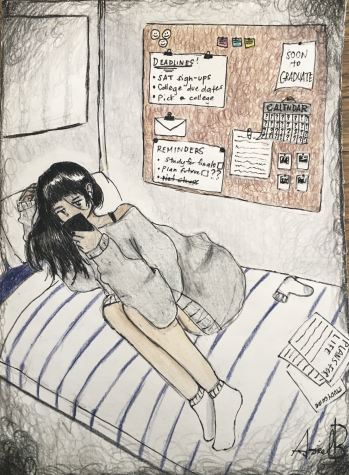

How “prepared” you are for college has less to do with the public school itself and more to do with what classes you choose to take.

There’s hardly a shortage of Advanced Placement and Dual Credit classes here at Kalani. You can build your schedule to be rigorous. The teachers do a good job of encouraging college preparedness; students should not be generalized and talked about as lowly or unprepared.

I think the majority of people who carry stigmas about public schools, such as that they are “rough” and “rowdy,” haven’t attended one. Two-thirds of lawmakers don’t send their children to the public schools in the districts they represent, according to KITV.

I think growing up with the classism that surrounds public school students has created fierce competition from both sides. And in this competition, public school students stand no real chance: we don’t have the nice things at our schools that private schools have. The struggle for air condition is everlasting; our facilities are worn down, our sports programs don’t attract elite athletes.

But inside these schools are many bright, hardworking students who deserve as much praise and credit.

I’ve been in the public school system since kindergarten. I’ve eaten the infamously awful school lunches, been in the lackluster bathrooms, used the ancient and inadequate technology. It has not destroyed my life. I do not feel like I or any of my peers have been given fewer opportunities to grow and succeed.

No more scoffing. Hawaii’s public school kids are not ghetto.

We receive care and attention. Bad people, bad kids, bad students: these things are not bred in public schools.

We, as a state, need to stop talking down to state-funded schools. We need to stop reinforcing the stigmas against low-income students and families, continuing age-old stereotypes surrounding the division of classes.

Stereotypes have no place in education, whether you go to a private or public school.