Cellphones should be OK.

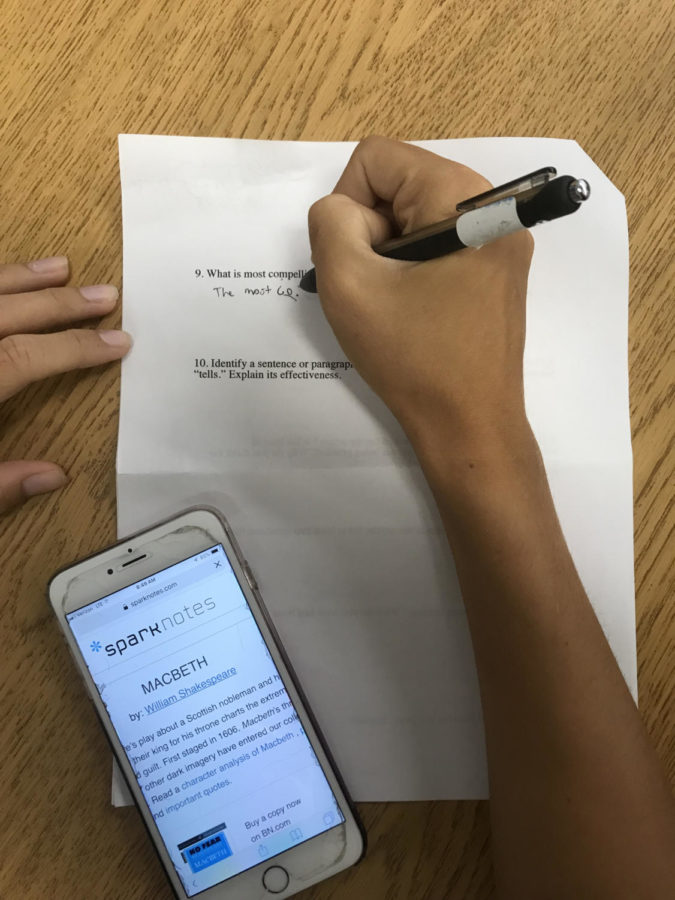

A student uses the Sparknotes website to help answer questions on a Macbeth worksheet in class. Photo by Serena Wong 2019.

May 20, 2019

How many times a day do you look at your phone? Just a quick glance? Chances are it’s an incredibly high number.

While in school, we are all told never to cheat and never to use our phone when taking a test. But what would you use in the actual world if you had to solve a math problem?

We believe cellphone usage shouldn’t be considered cheating because when we are actually out in the real world, and we have to calculate how many square feet of fence to buy at 40-cents a foot with only $10.47 in our pockets, 90% of the time we are going to use our phones to figure it out.

Your phone is your own personal supercomputer, so why waste it by not looking up things you don’t understand? That is why we believe that using your phone for tests and assignments shouldn’t be considered cheating.

You’re not gonna go to a foreign country and say, “I know I have my phone and all, but I’m gonna speak broken Spanish anyway.” Sure, what you learned in high school Spanish class will help, but chances are you’re gonna pull out your phone and type what you want to say into a translator.

People are becoming incredibly dependent on their phones — and that is a topic for another day — but we’re not going to ignore our phones if we don’t understand something. We’re gonna use it every chance we can get. We want a reason to pull it out and say: “Teach me Almighty phone.” OK, maybe we don’t say that, but you get the point.

Most times, we don’t have textbooks lying around waiting to teach us. But we can use our phones, which is arguably better. If someone wants to look up the history of Hawai’i, they’re gonna pull their phone out and look up what happened and then probably fall into the rabbit hole of history.

For our generation, there’s something different about reading text on our phone versus a book; something about it makes the information easier to invest in.

Teachers aren’t wrong for saying “no phones in my class” or variants of those words because it’s their class so if they say no, listen to them.

However, saying that kids don’t learn when given the answer, we say this: when you’re watching a murder mystery, do you get annoyed when at the end of the episode they tell you who did it, why they did it, and how they did it? No, you go, “Ha! I knew it was Timmy.”

People, especially kids, find it harder to learn when they aren’t helped along the way. Sure, some people understand everything easily, and to those kids, we say “Bravo!” However, other kids have a tremendously hard time figuring out certain problems. Sure, the teachers can help the students, but they usually teach the harder, more difficult-to-understand methods of solving equations, a method that takes ten steps to solve when that same student can find on the internet an easier, two-step way to get the right answer.

However, we students have to know when it is appropriate to pull out our phones. If a student has to write an essay and he is sitting there playing Candy Crush, he should push himself to work on the essay. If you use your phone irresponsibly, it’s understandable if you get in trouble or get your phone taken away.

However, if you use your phone for class work and get stuff done, you should be allowed to use it as much as you need.

To fix this, we propose that teachers give students the benefit of the doubt and let students use their phones for research and to help them complete assignments because in real life no one will tell us to put our phones away.

Students may abuse the phone rule and, instead of doing work, they will play on their phones, but we propose that everyone try a little harder to complete their work and then have fun after.