What’s in an Anglicized name?

February 14, 2023

Does having an English name make you American? Does having a non-English name separate you from being American? What does being “American” really mean? Names have power but what happens when those names are replaced?

America is a nation created by immigrants since the first founders of America were immigrants from Britain. America had always been an ideal modeled after the American Dream many other immigrants from around the world believe in. Thus, having an anglicized name is not necessary to be considered American.

Rajat Panwar, pronounced phonetically R-uh-j-uh-t P-un-w-aa-r, an author of the Harvard Business Review, believes strongly that names are a part of his identity.

“I appreciated my new acquaintance’s sensitivity to potentially mispronouncing [my name],” Panwar writes. “I also felt that he was asking me to strip away a part of my identity for his convenience. I politely declined [when a coworker asked to call me Raj]. It took him only two efforts, and about 30 seconds, to get it right. I wasn’t surprised.”

Panwar proposes three points: ask questions and repeat their name to familiarize yourself with the sounds, use phonetics, and be kind.

The use of phonetics is an easy way to learn “hard” names and, according to English Explorations, is the study of the range of sounds that words and letters form in speech patterns.

For example, my last name, Velasco, is pronounced phonetically Veh-LAH-skow.

Carnegie Mellon University’s Phonetics Spelling Instructions and How To Pronounce.com are good sources for finding the phonetic spelling of names.

Yuchen He (11), phonetically pronounced You-chen, moved to Oahu from China when he was four.

“My mom asked me if I wanted an English name and we were thinking about it,” He explains. “But it was too much work thinking about the new name.”

The process of “Americanizing” names is called the anglicization of names. It’s a common practice among Asian Americans who have immigrated or have immigrant parents in an attempt to assimilate. Some Jewish and European immigrants have also used this practice, according to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services.

“My name’s Japanese and it’s hard for people to pronounce and read it,” Kaede Mccall (11), phonetically spelled Kah-eh-deh, says. “When I go to a cafe and they need my name, I just say Kate because my name is too bothersome to explain and teach them how to spell it. And when somebody else gets the cup they are just going to say my name wrong anyways and I’m probably not going to hear them because it’s not my name.”

Mccall states that using a different name is “more convenient” and “easier” than explaining her name.

However, in doing so, names sometimes translate differently. He, whose name means “morning” in Chinese because he was born in the morning, wouldn’t be the same as an American name that looks similar to “Yuchen” because the meaning doesn’t translate.

The same applies to Mccall, whose name Kaede means “maple” in Japanese, which doesn’t have the same meaning as Kate, which means “pure” in English.

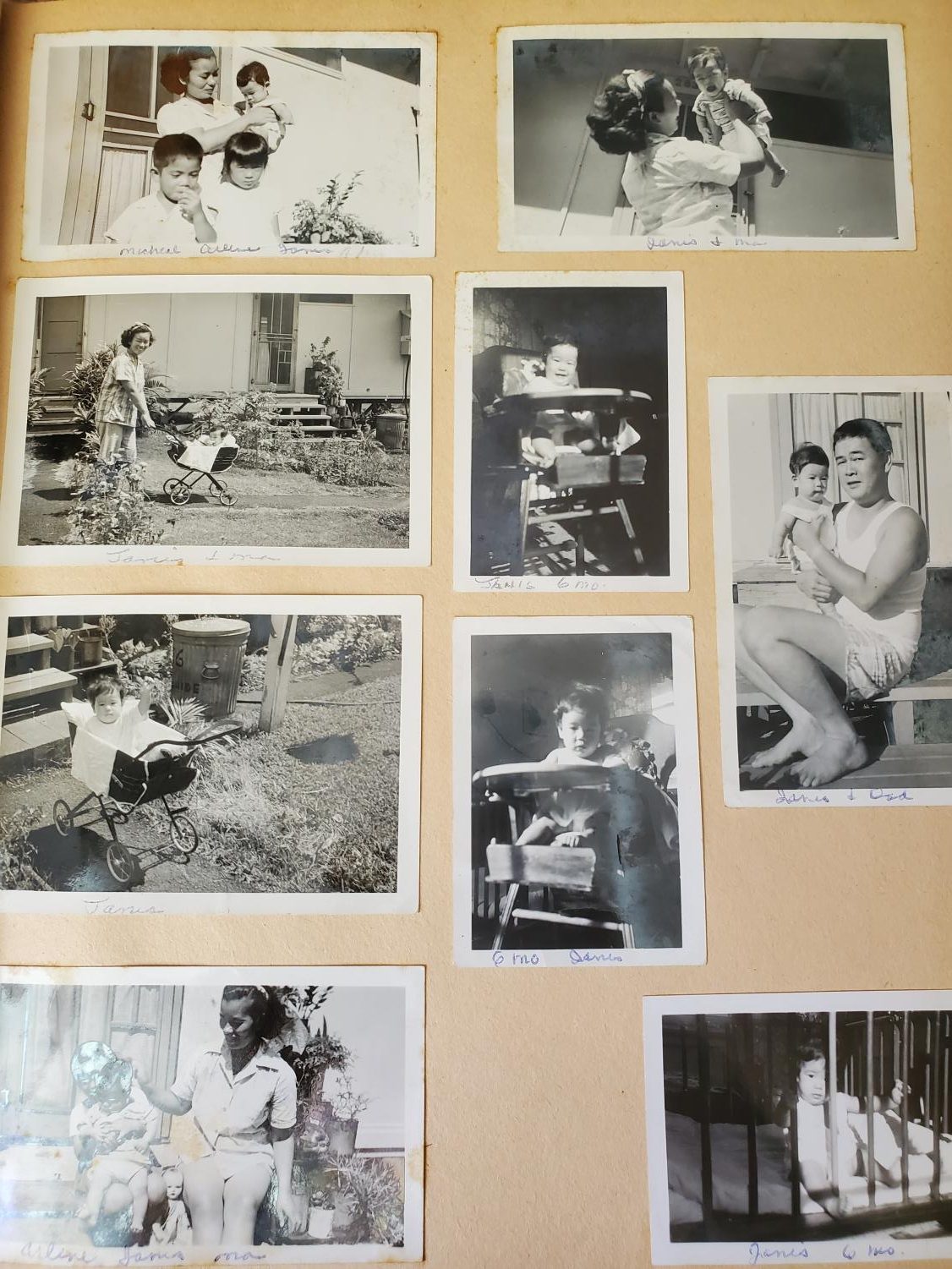

Janis Yahiku, daughter of Japanese immigrants Masako and Noboru Higashide, says that her parents anglicized their names because they wanted to “be identified more as American” due to World War II.

“It [the war] was against Japan,” Yahiku explains. “There was an internment camp in the islands, but my parents weren’t in one.”

According to Yahiku, Masako gave herself the name “Ellen” while Noboru called himself “Wane.” Their three children, Arlene, Janis, and Owen, were given American names to fit in while having Japanese middle names as a tie to their heritage.

Yahiku states that she and her older sister, Arlene, were named after American actresses by their father. Owen was named by their mother because she “liked” the name.

Anglicizing names is a very personal choice. Those for it believe it’s necessary to be considered American, but according to CNN style, anglicization was seen as a “survival tactic” to obtain their “American Dream” back then.

Professor Catherine Ceniza Choy at the University of California, Berkeley, specializes in Asian American and Asian diaspora studies. She believes that now is a time of change as current generations are beginning to realize the sacrifices their immigrant ancestors have made to become “American.”

Choy describes it as young Asian Americans realizing a “loss of heritage and culture” in their parents’, grandparents’, or even great-grandparents’ lives. Young Asian Americans are now taking strides to reclaim their heritage, some studying their grandparents’ original language, visiting family shrines, or even going by their birth name instead of their anglicized one.

“Names reflect your presence, your being, your history,” Choy affirms. “When people constantly do that, they’re not acknowledging you—as a person, as a human being.”

Sources: