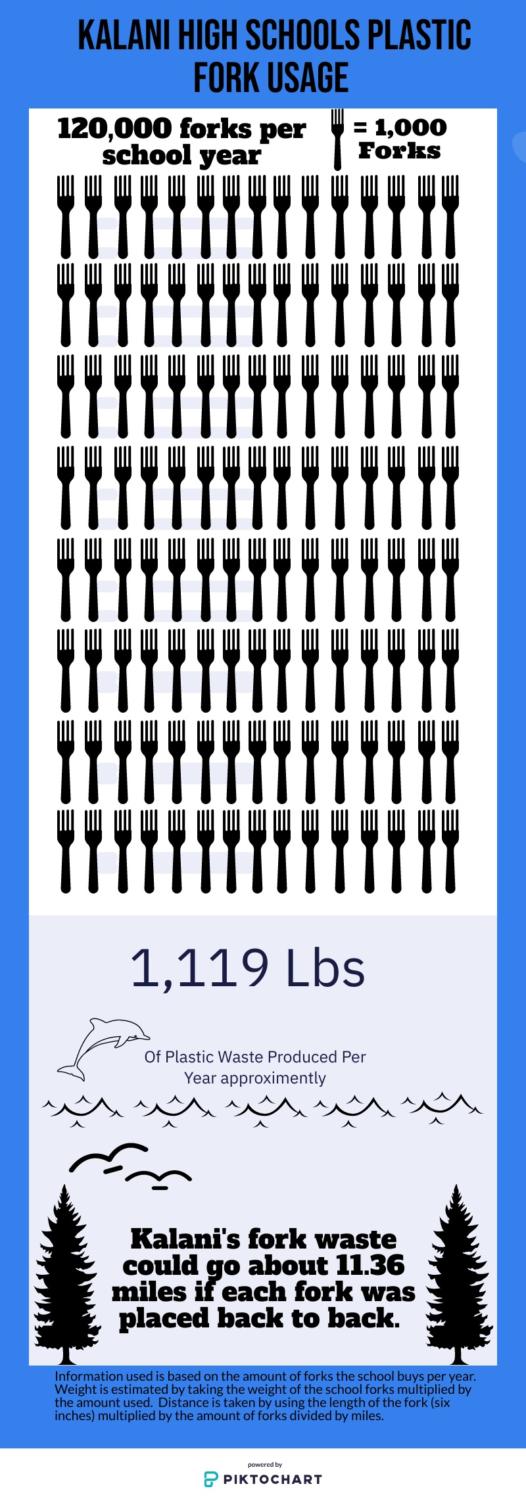

Kalani produces 1,119 lbs of plastic waste per year

November 26, 2019

Kalani High School has a large plastic footprint, using approximately 120,000 plastic forks per year, according to Brenda Nagasawa, the School Food Service Manager.

Plastic waste is a growing issue: the ocean is predicted to have more plastic in it than fish by 2050, according to the MacArthur Foundation. If Kalani, and the world, does not work to end its reliance on plastic we are going to continue to see a domino effect of environmental issues.

All of Kalani’s waste ends up at the Honolulu Program of Waste Energy Recovery (H-POWER), according to Nagasawa. H-Power’s goal is to “reduce the volume of municipal waste oh Oahu” according to Hawaiianelectric.com, and incinerates up to 3,000 pounds of waste a day.

While Kalani’s trash might not end up in the ocean, it does have another harmful impact.

According to Zero Waste Oahu, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that H-POWER produces three times more greenhouse gas emissions than Kahe, one of Oahu’s oil-fueled power plants. Greenhouse gasses are what cause the earth’s atmosphere to warm, causing a domino effect of other issues such as ice caps melting, sea-level rising, and ocean acidification.

When Kalani students heard the number of forks used at school per year, many were surprised.

“I wasn’t aware of that and that’s absurdly large,” Koa Souza (10) exclaimed.

Kaiya Arias de Cordoba (10) says plastic waste makes her “disappointed” and “angry.” She usually brings her lunch to school to avoid plastic waste.

“We live on a small island and should know better than to use so much plastic,” Arias de Cordoba shared. “There are better options than plastic. Or, if we use the plastic, we should always reuse it!”

Lauren Vierra (10) and Lucy Dooley-Carl (9) came up with the idea: tell students to bring reusable forks and, after a two-week warning period, start charging for plastic, an idea modeled after Hawaii’s new plastic bag law.

“Clubs could even sell reusable forks as a fundraiser for students who forget,” Vierra added.

Another idea proposed by Arias De Cordoba would be for the school to get reusable forks and form a committee to wash them. Other students such as Souza don’t believe students would return the forks.

A good incentive for students could also be class points.

“Every time you buy a lunch, the lunch workers would mark whether or not you brought your own fork no not,” Arias de Cordoba explained. “Whichever grade had the least amount of plastic forks would win something.”

Despite alternatives, some are still wary that high schoolers would give up the convenience.

“There are solutions out there,” Souza stated. “But honestly, I don’t think that any of them would stick in a high school setting because you know high schoolers don’t want to do extra things. Teens are picky brats.”

One solution that would eliminate any student effort would be the cafeteria switching to biodegradable forks, something Kalani’s Green Team was attempting to do. The challenge is dealing with the price difference between plastic and biodegradable options.

Wilson Tran (11), founder of the Green Team, encourages students to reduce plastic waste.

“Bringing your own fork is an individual choice that could make a much larger impact if many people did it,” Tran shared. “And honestly I think that’s pretty cool to be apart of.”